|

The Mirage F1 came about when plans for

the successor to the Mirage III proved too expensive and unpopular to

the French Air Force. It was a time when new technologies were being

tested including vertical take-off and swing-wing concepts. Dassault

developed the F1 as a private venture to offer a cheaper multi-role

aircraft. From the outset it was designed to obtain the best operational

efficiency and the widest flexibility. The idea being that even a small

fleet of these aircraft should represent an important military threat.

Something which was proven later in Angola! It was to be able to operate

from short rough strips which the twin pulled wheel on the main gear

together with medium pressure tyres plus low landing speed (145 kts)

enabled it to do. It provided minimum and fully air transportable ground

handling equipment together with a self starting system. It provided

a short turn around time of about 15 minutes between two identical missions

together with pressure refueling of about six minutes. An engine change

involving four men took about three hours The SDAP automatic testing

unit enabled automatic trouble shooting in the field. The GAMO alert

unit allowed the Mirage F1 to be scrambled in less than 2 minutes. Thus

it was to prove an ideal 'Bush' warfare aircraft capable of operating

for extended periods away from itís home base, as was the case for the

SAAF operating in Namibia.

The Mirage F1C prototype made itís first

flight on the 23rd of December,1966. During September 1967, the French

Air Force expressed interest on the Mirage F1C as an all weather interceptor.

This was adequately provided by the use of the Cyrano IV radar. The

second prototype F1-02 first flew on the 20th March,1967 and the third

prototype F1-03 flew on the 18th of September,1969. On the 17th June

1974, the final prototype F1-04 flew and this became the production

version. This was to become the first Mirage F1 ever flown by a South

African when Zach Repsold flew it on 6 October 1971. This differed from

the others by using slotted slats. On the 14th March 1974, the French

Air Force received the first Mirage F1. The French Air Force Mirage

F1C first saw combat during operation Manta in August 1983. This was

when they were used for strafing an enemy column.

First Prototype Mirage F1, Saint Cloud 23 December 1966. Photo: Keystone Press Agency / P. Dubois collection |

First prototype aircraft. Photo: Dassault Aviation /

P. Dubois collection |

Second prototype aircraft. Photo: P. Dubois collection. |

Third prototype aircraft, Le Bourget 29 May 1973.

Photo: P. Dubois Collection. |

First pre-production aircraft. Photo: Dassault Aviation /P. Dubois collection |

Fourth prototype and first production F1. This

particular aircraft was also the first Mirage F1 to be flown

by a South African. Photo: Dassault Aviation |

In July 1973, in what was to be known

as the deal of the century, Dassault tended the Mirage F1E or the Mirage

M53 as it was later to be known as a contender for the new European

fighter aircraft required by Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands and Norway.

To meet this requirement, the Mirage F1 was equipped with more sophisticated

avionics and a more powerful engine, the M53 engine. This engine is

shorter than the standard ATAR 9K50 and required larger air intakes

and a shorter rear fuselage. Unfortunately, this lucrative deal was

won by the American F-16.

In 1971, South Africa began looking for

a replacement for the Mirage III . The Mirage F1 was an improvement

of the Mirage III in that it has an increased speed, increase pursuit

flight time an high mach which was tripled , and a ground mission range

doubled, Take off length 30% less, with 25% less approach speed and

increased maneuverability. On the 27th June 1971, Dassault and SNECMA

announced a technical cooperation agreement with South Africa for the

license manufacture of the Mirage F1 and engine. The intention being

to produce up to 100 Mirage F1ís.

SNECMA ATAR 9K 50/ Photo: Dassault Aviation |

Mirage F1-E fitted with a SNECMA M53

engine. Photo: Dassault Aviation /

P. Dubois collection |

The 1977 arms embargo caused this license

to lapse and unfortunately the Atlas Mirage Program did not move beyond

the assembly stage. The South African Air Force acquired 16 Mirage F1-CZís

(Serial 200-215) and 32 Mirage F1-AZís Serial 216-247). Mirage F1-CZ

'200' was the main project aircraft, whilst Mirage F1-AZ '216' was used

as the project aircraft for the 'AZ' fit. Due to the approaching Arms

Embargo, Dassault rushed the F1-AZ delivery which not only led to teething

problems with this ground attack variant but also caused problems with

the manning of the Mirage III fleet which was later overcome by Operation

Sand which enabled the Rhodesians to maintain the Mirage III CZ fleet.

Mirage F1-CZ '200' salvo drop of eight 400kg bombs, during acceptance

trials in France. Photo: Dassault Aviation Film footage. |

Mirage F1-CZ '200' salvo firing of

Matra 68mm rockets, during acceptance trials in France, 1975.

Photo: Dassault Aviation. |

Mirage F1-CZ '200' at the Paris Air Show 6 June 1975.

Photo: P. Dubois Collection. |

Mirage F1-CZ '200' seen at Istres 1974 during acceptance trials.

Photo: P. Dubois collection. |

Mirage F1-AZ '216' during acceptance trials in France 1975.

Photo: Peter Greve/P.Dubois collection. |

Mirage F1-AZ "216" with the 14 bomb configuration during acceptance

trials in France. Note the camera's fitted directly below the

cockpit. which recorded the bomb release. Photo: Dassault Aviation/P.

Dubois collection. |

Delivery began under great secrecy on

4 April 1975 when two Mirage F1-CZís were flown to South Africa in a

SAAF C-130 Hercules. Delivery ended in October 1976. South Africa maintained

great secrecy over this aircraft and only revealed a new 'Mirage-type'

during a fly past at the Ysterplaat Air Show in October 1975. It was

only in April 1977 that the press could visit the production line in

Kempton Park and even then the Mirage F1-AZ remained classified until

1980.

THE MIRAGE F1-CZ

South Africa was the launch foreign customer

for the Mirage F1-C with the test aircraft for this project being Mirage

serial '200' and whilst still being kept secret from the South African

public, this aircraft appeared in several publications such as 'Paris

Match' and it was also used as a display aircraft at the Paris Air Show

1975.

On the 4 April 1975, 3 Squadron became an autonomous unit once more

with the arrival of Mirage F1-CZís serial 204 and 205 from the Atlas

Aircraft assembly line at the then Jan Smuts Airport. The rest following

at intervals until 1977 when Mirage F1-CZ serial '200' finally joined

the fleet, thus completing the order for 16 aircraft. Serials 200-215.

|

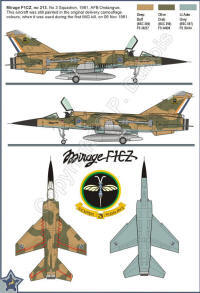

Mirage F1-CZ, No 213, No 3 Squadron, 1981, AFB Ondangwa.

This aircraft was still painted in the original delivery camouflage

colours

when it was used during the first MIG kill, on 6th November

1981.

Diagram by William S Marshall. |

All aircraft were delivered in an olive

drab/ deep buff scheme with blue/white springbok castle insignia. The

squadron emblem being applied in South Africa. During the early eighties

the scheme was changed to an air superiority blue/grey scheme with false

canopy painted on the underside. The insignia was sprayed over to make

it low viz. The first Mirage F1-CZ to receive this scheme was '203'.

The SAAF Mirage F1-CZ wasted no time

getting operational and on the 3 November 1978, five Mirage F1-CZís

were deployed to AFB Ondangwa in SWA/Namibia tasked with providing escort

for reconnaissance flights over Southern Angola. From 1980 these deployments

became regular with operations such as 'Smokeshell'. The tasking was

normally as escort aircraft but due to teething problems with the Mirage

F1-AZ, it was soon tasked with pre-emptive strikes against the enemy

using Matra M155 rocket pods or 250 kg bombs.

A Cinethoeodolite image of Des Barker firing a V3C missile at

a high speed drone. Photo: OTB/P.Dubois collection. |

Mirage F1-CZ drone kill, Pilot Des Barker.

Photo: P. Dubois/TFDC. |

On the morning of the 6th November 1981

the Mirage F1-CZ got itís first test as an interceptor. Two Mirage F1-CZís

flown by Major JJ Rankin and Lt. J du Plessis were scrambled from AFB

Ondangwa to intercept two MiG-21MFís. Lt. du Plessis tried twice to

engage one of the MiG-21MFís but on both occasions his missiles failed

to engage. Major Rankin flying Mirage F1-CZ '213' could also not

lock his missile due to the proximity of the sun but opened fire with

his 30mm DEFA cannons which caused Lt. Danacio Valdezís MiG-21MF to

explode and was seen to break in half. Lt. Valdez was seen to eject

but did not survive. This was the first confirmed SAAF kill since the

Korean War.

|

|

Mirage F1-CZ's first kill.

Photo: SAAF/P. Dubois collection.

|

During the afternoon of 13 May 1982 the

F1-CZís bagged their second kill. This was the Angolan Mil Mi-8 helicopter

serialed either H-516 or H-518 which was believed to be carrying senior

officers. Captain M Louw flying Mirage F1-CZ '206' and Lt. Jon Inges

flying '210' were tasked with locating and destroying the helicopter

in the Cuvelai area. The helicopter was located with rotors running

on the ground. Lt. Inges attacked first but was off target. Captain

Louw then followed, destroying the helicopter in a hail of 30mm fire.

Mirage F1-CZ's second kill.

Photo: SAAF/P. Dubois collection. |

Angolan Mil Mi-8. Photo: SAAF/P. Dubois collection |

Events on the 5th October 1982 are not

so clear and much controversy remains over what actually happened. There

is also much contradiction amongst Cuban and South African sources.

The author has done much research on this and Iíve tried to piece together

what happened based on the information available. It is of course entirely

up to the reader to choose what they want to believe. Due to the harsh

restrictions of Cuban authorities and Johan Rankinís reluctance to discuss

the matter Iíve had to rely almost solely on written statements by the

parties involved, with the noted exception of the excellent feedback

from Cobus Toerien and the detail given by Barbaro Perez Duran. Some

information may have also been lost//misinterpreted in the translation

from the original Cuban text. Whatever happened that day, both parties

agree that at least one MiG-21bis was written off. The South Africanís

providing convincing gun-camera footage of the MiG-21bis exploding,

albeit a clean explosion without debris as if a fuel explosion. That

said it should be noted that no sane pilot would remain with his aircraft

after such an explosion especially when considering that Lt. Raciel

Marrero Rodriguez was a Third Class Pilot with only 320 flying hours!

Surely he would have ejected, wouldnít you? Also they had been flying

with full burner for six minutes, did Lt. Rodriguez have sufficient

fuel to make it back to Lubango? Cuban sources insist that he returned

to Lubango were witnesses said that the aircraft looked like a sieve

from all the projectile holes ripped into it. The remains of such a

MiG were seen at Lubango during the nineties.

|

Angolan

MiG-21bis. Photo: Paul Dubois. |

During this period the Radar at Cahama

was experiencing many difficulties and most of the MiG-21ís were scrambled

to false alarms and thus the more experienced pilots tended to bully

the younger pilots into doing these alerts. On this occasion it was

for real. At 10h28 am SAAF aircraft had been detected between Virey

and Tchibemba (The Mirage F1-CZís) and a second pair heading for Cahama.

(The Canberra or Canberraís depending which version you wish to follow.)

This was the Reconnaissance Canberra from 12 Squadron flown by Cmdt.

Bertus Burger and navigator Maj Swanepoel tasked with a photo-reconnaissance

of Cahama, together with one other? (Where two Canberraís involved?)

Their escort was two Mirage F1-CZís from 3 Squadron, flown by Maj. Johan

Rankin and his wingman Capt. Cobus Toerien. Maj. Rankin was flying Mirage

F1-CZ '203' which was nicknamed 'Le Spectre' as it had the new air superiority

blue/grey scheme, whilst the other Mirage still had the old scheme.

The Mirage escort was late due to Capt Toerien having problems starting

his Mirage and it is possible that this led the Angolanís to believe

that the Canberra was unescorted.

At approximately 10h42 am Lt. Raciel

Marrero Rodriguez, call sign 846 and Lieutenant Gilberto Ortiz Perez,

call sign 324 got airborne. Lt. Barbaro Perez Duran was the GCI controller

(Leon 5) and he directed them to the Cahama region. At this point the

South African Dayton Radar picked them up and the controller Captain

Les Lomberg instructed the Canberra to head south whilst vectoring the

Mirage F1-CZís north climbing to 30 000ft. At this point two other MiG-21ís

where placed on standby at Lubango. When Lt. Duran advised the MiG-21ís

that the target was 10 kmís away they jettisoned their auxiliary tanks.

Major Rankin picked up the two MiG-21ís 5nm away and at the same level

to his right. The Mirageís then jettisoned their auxiliary tanks and

went into afterburner whilst making a hard right hand turn. Lt. Perez

visually located the Mirages when they released their auxiliary tanks

and then the MiG-21ís also turned right with maximum turn.

As the Mirage F1ís began maneuvering

the MiG-21 pilotís lost visual with the Mirage F1ís. The MiG-21 began

a new turn whilst searching. At the crucial cross they flew so close

that Captain Toerien could see Lt. Rodriguez helmet and in fact they

almost flew into each other. At that point Lt. Rodriguez was looking

downward. Two minutes after having lost sight of the Mirageís, Lt. Perez

looked through his periscope and saw Maj. Rankin between 800 and 1000

metres behind him. He advised Lt. Rodriguez, did an abrupt semi reversal

and leveled out. Major Rankin fired two Matra 550 missiles at Lt. Perez,

one at 3000m and the other at 1500m, whilst doing in the region of Mach

1.2 at 30 000 amsl. The first being fired on the edge of the missiles

parameter and this failed after the motor burnt out. The second missile

was fired in the heart of the envelope, almost too close for the height

and speed and exploded immediately behind Lt. Perezís MiG-21. Lt. Perez

was seen to dive towards Lubango trailing smoke. He had not felt the

impact to the right stabilizer and therefore did not realize that he

had been hit. His MiG-21bis serial C-47 landed at Lubango without difficulty.

During the combat his aircraft had pulled a maximum of 6 Gís.

At this point two more MiG-21ís were scrambled but failed to locate

the Mirageís once in the area., returning once they were low on fuel.

Did Cuban witnesses mistake these two for the original MiG-21ís scrambled

thus believing that they had safely returned?

When Lt. Rodriguezís located the Mirageís they were directly in front

of him and at the same time he noticed a very bright explosion to his

left. He noticed the two Mirageís separate with one going up and the

other to the left, his right, and before losing sight of them he noticed

them turning to the right. At this he kept turning right at maximum

speed, whilst trying to communicate with the GCI controller. When he

finally got through, Lt. Duran ordered him descend to 2000 metres at

270 degreeís and to search that area. At this point Capt Toerien had

caught up with Maj. Rankin. The new low viz scheme on Maj. Rankins Mirage

started to pay dividends! Lt. Rodriguez was attacked by Maj. Rankin

at around 500metres but he could only detected Capt Toerien's Mirage

in his periscope at around 1800 metres and he thought the 30mm Cannon

fire was coming from 1800metres. Lt. Rodriguez was turning hard at about

60-70 degreeís when he realized that Maj Rankin had entered his turn

radius.

Due to the vertical form of his left

wing, the wing became perforated and he also felt the impact from his

tail being hit with a momentary increase of speed. At this point he

advised Lt. Duran that he had been hit and was descending. Lt. Rodriguez

claims that he still had control of the aircraft although flames were

shooting from the tail and he was trailing black smoke. All hydraulics

and oil pressures were normal, the only difference was a tendency for

the aircraft to bank right. When about 45kmís away from Lubango he advised

control that he was worried that the damage to his left wing was going

to interfere with the lowering of his undercarriage. (This fitís with

the radio messages picked up by South African forces and attributed

to Lt. Perezís MiG-21.) Lt. Rodriguez claims to have landed safely.

His aircraft having pulled a maximum of 6.7 Gís during the combat. Major

Rankin had tried to fire at 350m but had pushed the trigger safety guard

back by mistake.

After clearing the guard and firing he

was down to 230m. The fuel started leaking from the MiG-21 and then

exploded, Major Rankin flew through the fire ball, causing a compressor

stall. He then cut the engine and did a hot relight before heading towards

Ondangwa. Capt. Toerien had followed the MiG-21 which had turned right

(Northwards) whilst rapidly descending trailing a large plume of black

smoke from the left rear of the fuselage, but he turned back once Maj

Rankin reported his compressor stall. At this point Capt. Toerien had

lost sight of Maj. Rankin and was concerned about the other MiG-21ís

which the South African radar had now picked up. Maj. Rankin then climbed

past him at his right abeam position before both returned to Ondangwa

on minimaís. The air combat had lasted around six minutes.

The Cuban pilots used rigid doctrine which did not allow for individual

initiative, always under the control of the GCI Controller, thus no

matter their experience, their tacticís always remained the same. Due

to this disastrous attempt at intercepting the South Africanís, Colonel

Bilardel, OC Lubango was removed from his post and demoted.

Like every year, the Bush War saw an escalation and by 1987 it was heading

for conventional war status. From 1987 the Cubans deployed two MiG-23ML

units to Angola forming 12th and 13th Squadrons of the FAPA-DAA, part

of the 25th Air Combat Regiment. Some fifty MiG-23MLís were supplied

direct from the USSR. Up until this point the Angolan Air Force had

chosen to avoid the SAAF but now the Cubans goal was to challenge the

SAAF air superiority over the battle fields. The main base was at Menongue

which was heavily defended against air attack. It is clear that the

Cubans plan was to start a war of attrition, something that due to the

Arms Embargo the SAAF was never going to win. By the end of 1987 the

Cubans had added another 30 MiG-23MLís

to the Angolan fleet.

The SAAF met this threat by deploying Mirage F1-CZís to Rundu AFB in

the Eastern Caprivi. They also started upgrading this facility, something

they should have done earlier, as events were to prove. The MiG-23ML

crews preferred to use their superior speed for slash and dash type

attacks on the SAAF, whilst the SAAF preferred to 'mix' it with the

enemy. On the 10th September 1987 a Mirage F1-CZ fired an R.550 missile

at a MiG-23ML but without results. Events took a dramatic change on

the afternoon of 27th September 1988, when four Mirage F1-CZís where

scrambled from Rundu to intercept a pair of MiG-23MLís flown by Maj.

Alberto Ley Rivas and Lt. Juan Carlos Chavez Godoy who were providing

CAP for some helicopters. Capt. Arthur Piercy in Mirage F1-CZ '206'

was wingman to Cmdt. Carlo Gagiano and it was this aircraft that Maj.

Rivas saw during the initial engagement. The Mirage F1-CZ was in front

of him but slightly higher. Maj. Rivas fired one missile. (According

to South African sources an AA-8 missile.) Capt. Piercy saw the bright

flash as two missiles were fired from the frontal sector, one passing

over Cmdt. Gagianoís aircraft, the other exploded alongside Capt. Piercyís

Mirageís tail section, this was followed by Maj. Rivasís MiG flashing

past.

A Pencil

sketch by artist Geoff Pleasance depicting the attack by

Maj. Alberto Ley Rivas against Capt. Arthur Piercy. |

Angolan 'Vet', MiG-23ML '223' seen at the DAAFAR Museum, Havana.

Photo: Paul Dubois. |

MiG-23ML '223' with star indicating a successful mission in

Angola/ DAAFAR Museum, Havana. Photo: Paul Dubois. |

Capt. Piercy states that the combat lasted

about 40 seconds. His aircraft plummeted earthward before he was able

to recover it. He returned to Rundu AFB at extreme low level when the

electric pump, right side fuel pump and hydraulic H-2 system failed.

He also had no drag- chute as this had been damaged in the missile blast.

The aircraft came down fast on the 2000m runway, overshot and went through

a perimeter fence before the nose wheel struck a rock causing the seat

to eject. The parachute had no time to open which resulted in serious

injuries to Capt. Arthur Piercy. Mirage F1-CZ '206' was written off

but parts were used later to rebuild Mirage F1-CZ '205' which had been

damaged in a fire.

The superior speed of the MiG-23ML , with there frontal aspect air-to-air

capability, coupled with the very poor performance of the South African

air-to-air missiles meant that the SAAF could no longer afford to risk

itís precious few Mirage F1ís in air to air combat. This severely limited

their daylight operations. The Mirage F1 remained a threat to the MiG-23

and as long as the SAAF retained the numbers they would act as a deterrent,

thus the SAAF needed to avoid a war of attrition.

Claims have even been made by authors such as Timothy Good about two

Mirage F1-CZís dueling with UFOís near Ludoritz (Namibia) on 18 June

1977. Even though no Mirage F1-CZís had been deployed to Namibia at

that stage, nor had any been lost during 1977.

During almost ten years of continuous combat, the SAAF only lost one

Mirage F1-CZ to enemy action. A further three were lost in accidents

and one ('214') was broken up in 1992 as part of an engine upgrade program.

The aircraft lost where;

'200' w/o on 15 February 1979 after the aircraft stalled.

'206' aircraft damaged severely due enemy action.

'208' w/o on 4th November 1980 after mechanical failure, pilot ejected.

The Mirage F1-CZ was withdrawn from service on 9th September 1993 when

3 Squadron was disband, however Mirageís '205' and '209' continued to

operate as part of 190 Squadron until 1993. These aircraft were used

for the clearance trials of various missiles.

|

Mirage F1-CZ

'209' showing the two different schemes worn by the Mirage F1-CZ.

Photo: P. Dubois collection. |

THE MIRAGE F1-AZ

The Mirage F1-AZ is probably better known in the UK for the black painted

jet in the French car manufacturer commercial which was shown on TV.

The Mirage F1-AZ is optimised for ground attack and was designed to

meet a South African requirement. Due to the 1977 arms embargo this

project was rushed before all the 'gremlins' in the ground attack suite

had been resolved, this caused a few initial problems in South Africa.

The first Mirage F1-AZís to arrive in South Africa, came by sea during

March 1976 and were assembled at Atlas Aircraft near Johannesburg. Thirty-two

Mirage F1-AZís (Serial 216-247) were delivered from November 1975 until

October 1976.

All Mirage F1-AZís went to 1 Squadron

at Waterkloof AFB before finding a permanent base at the ultra modern

Hoedspruit AFB. The first aircraft '216' was the project aircraft and

Cmdt. Piet Huyser was the South African project officer for this aircraft.

He was responsible for the cockpit layout. Two 'dummy' Mirage F1-AZís

were given the serials '248' and '249', these were used as decoy aircraft.

|

Mirage F1-AZ

decoy.

Photo: Paul Dubois. |

Whilst the local South African magazine,

'Scope' covered the Mirage F1 in their edition on 29 July 1977, it was

only in 1980 that the South African public became aware of the existence

of the Mirage F1-AZ and even then itís air-to-air refueling capability

was kept secret. Not only was the Mirage F1-AZ a South African concept

but they also funded the design and development of the roller map and

nav/weapon system. The fundamental difference between the Mirage F1-CZ

and AZ variants is the removal of the expensive Cyrano IV radar, being

replaced with the smaller ESD AIDA 2 target ranging radar. The AIDA

radar still gave secondary air-to-air capability. Of greater value to

the SAAF, especially during the later years was the additional fuel

capacity coupled with the retractable air-to-air refueling probe.

|

Picture showing the retractable refueling probe.

Photo: P. Dubois |

The extra fuel being provided by an additional

fuel tank behind the cockpit. The ground attack suite consisted of the

Doppler effect ESD Navigation system, Thomson CSF laser sighting, SFIM

inertial control unit, Thomson CSF 129 HUD, moving map display and two

Crouzet/Thompson computers. This system enabled a target to be located

from 3 miles for an automatic bomb release.

Maj. Gawie Winterbach flew the first Mirage F1-AZ acceptance flight

in Mirage F1-AZ '216' on 7 October 1975 and again on the 24 March 1976

when he became the first to fly a Mirage F1-AZ in South Africa. The

Mirage F1-AZ began in-flight refueling from Buccaneer aircraft on 23

August1976 and from 1986 they also used Boeing 707 tanker aircraft.

|

Mirage F1-AZ's

refuelling from a Boeing 707 tanker.

Photo: P. Dubois |

On the 6th July 1978 the Mirage F1-AZ

carried out itís first operational sortie from MíPacha AFB and the last

was flown from Grootfontein AFB on 23 March 1988.

During the last seven months of the war 683 combat sorties were flown,

delivering 3068 bombs. It is estimated that over this period more than

100 SAMís had been fired at them. The SAM was the greatest threat faced

by the Mirage F1-AZ, with Mirage F1-AZ ď245Ē being shot down by a SA-13

missile. Mirage F1-AZís ď237Ē and ď234Ē had a lucky escape during 1980

after being hit by SA-3 missiles. Capt. Du Plessis received the Honoris

Crux for saving his valuable aircraft. To counter this ever increasingly

sophisticated SAM/AAA/Radar network not only were the tacticís changed

but aircraft were also upgraded. The original BF radar detector was

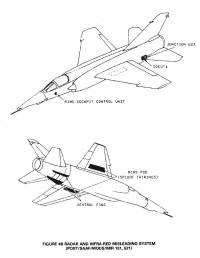

replaced with the Radar and Infra-red Misleading System better known

as RIMS. This system consisted of a junction box fitted to the rear

port fuselage and a dispensing pod located under each wing on station

zero.

RIMS Chaff. Photo © D. Coombe |

Diagram of RIMS/ Atlas Aircraft |

RIMS Chaff. Photo © D. Coombe |

RIMS Chaff. Photo © D. Coombe |

RIMS on tail, known as the 'cats balls'. Photo © D. Coombe |

This was not popular with the pilots

because it created a tremendous amount of drag. The under fuselage keels

were replaced with larger ones which held flare/chaff dispensers inside.

This system was fitted to both Mirage F1 types. Some Mirage F1-AZís

carried an ELT/555 (V)3 jamming pod under the port wing. Added to this

the Mirage F1-AZ crews changed tacticís to use the long toss bombing

profile or Vergooi as the SAAF called it. This involved pulling up the

aircraft around 4nm from the target and literally ďtossingĒ the bombs

towards the target. The aircraft also received a new camouflage. Whilst

various schemes were used, the final scheme was with all upper surfaces

retaining the olive drab and dark earth camouflage and all under surfaces

and sides being blue/grey.

|

ELT/555 (V)3 jamming pod. Photo: Electronica/ P.Dubois collection |

The Mirage F1-AZ also proved to be a

very useful interceptor. On the 8th July 1981, Lt. Adriano Francisco

Bomba of the Mozambique AF flew his MiG-17, serial '21' from his base

near Maputo and defected towards South Africa. Two Mirage F1-AZís flown

by Maj. F Pretorius and Capt. H Louw were returning from a training

exercise when they got diverted to Intercept the MiG-17. The MiG-17

was 40km inside South Africa when intercepted. After exchanging hand

signals Lt. Bomba was forced to land at Hoedspruit AFB. After much evaluation

the MiG-17 was returned by road to Mozambique.

|

Mozambican

MiG-17 being tested by Cmdt Bob Mason SAAF.

Photo: P. Dubois Collection. |

Then again on the 31 March 1981, two Mirage F1-AZís intercepted a Zimbabwean

AF CASA 212 and forced it to land at Hoedspruit AFB after asserting

that the aircraft had 'strayed' into South African airspace, it was

allowed to continue to Zimbabwe.

On the 25th February 1987 three Mirage F1-AZís fired several V-3B missiles

at a group of Angolan MiG-23MLís without success. This was repeated

again on 25th February 1988 when South Africaís ace (Rankin) tried his

luck again, this time in a Mirage F1-AZ.

He fired a missile at an Angolan MiG-23ML and even tried his 30mm canon

again but this time without success. Various other unsuccessful attempts

were made during the 1987-88 period. Mirage F1-AZ '220' even received

the same grey/blue air superiority scheme as used by the Mirage F1-CZ.

On the 30th July 1994, four Mirage F1-AZís escorted President Mitterrandís

Boeing 747 into Cape Town.

After the war, plans were made to upgrade the Mirage F1 fleet by replacing

the Snecma Atar 09K50 engine with the SMR95 engine which was based on

the Klimov RD-33, and the integration of the Russian R-73 air-to-air

missile. Fittingly the project aircraft for this was once again Mirage

F1-AZ '216'. Mirage '216' became known as 'Super Mirage F1'. Echoing

events of 1973 with the Mirage M53, sadly this project came to an end

when after 22 years of service the SAAF withdrew the Mirage F1-AZ from

service on the 25th November 1997. Thus ending the SAAFís 35 year association

with Mirage aircraft.

South Africa's 'Super' Mirage F1

with SMR-95 engine.

Photo: P.Dubois Collection. |

Closer view of Super Mirage F1 engine. Photo: P. Dubois. |

Last day of F1-AZ in service. Photo: Paul Dubois. |

Another project involved fitting an advanced

avionics suite to Mirage F1-AZ '235', this system was introduced to

the Spanish AF Mirage F1ís. Mirage '235' was given the unique white

and arctic blue scheme, earning it the nickname as the worlds fastest

dairy cart.

After 22 years of service, only eight Mirage F1-AZís were lost, one

due to enemy action.

Those lost were:-

'221' w/o 5th February 1992 after a bird strike, pilot ejected.

'222' w/o 4th April 1985, pilot ejected.

'223' w/o 19th March 1988, aircraft flew into the ground when returning

from Angola.

'224' w/o 9th June 1993 after aircraft ingestion of shrapnel during

bombing exercise, pilot ejected.

'228' w/o 13th February 1984, pilot got disoriented in bad weather and

ejected.

'234' w/o 23rd November 1993 when aircraft flew into the sea during

a low level maritime strike exercise.

'234' Pilot ejected but lost at sea.

'245' Shot down by SA-13 missile, pilot was killed.

'246' w/o 15th February 1979 after engine failure, pilot ejected. This

was the first Mirage F1 lost by the SAAF.

Mirage F1-AZ '245' shot down by a SA-13 missile. Photo: P.Dubois

Collection. |

|

Of the 24 remaining aircraft, 22 were

offered for sale in 1997 and in 2002 Aerosud purchased them with the

intention of returning 18 of them to service. So far they have sold

eight aircraft to the Gabonese Air Force.

Those known to have been delivered are:-

'239' which went to Gabon in August 2006 as TR-KML with about 1450 airframe

hours.

'241' which went to Gabon in August 2006 as TR-KMM with about 1544 airframe

hours.

'236' which went to Gabon in November 2007 as TR-KMN with about 1406

airframe hours.

'244' which went to Gabon in November 2007 as TR-KMO with about 1591

airframe hours.

This aircraft was one of the last two aircraft

to receive a service at Atlas Aircraft just months before retirement.

Gabon Mirage F1-AZ ex '239'. Photo: Cobus Coetzee. |

Gabon Mirage F1-AZ ex '241'. Photo: Cobus Coetzee. |

GENERAL PHOTOS

The pitiful 'Angolan War' display

at the DAAFAR Museum in Havana.

Photo: P. Dubois. |

Mirage F1-AZ '227'. Photo: P. Dubois. |

Mirage F1-CZ '212'. Photo P. Dubois Collection |

Mirage F1-AZ's taxi back for the last time, on 25 November

1997, end of an era. Photo: P. Dubois |

| |

|

By Paul Dubois

With thanks to: Luc Berger,

Des Barker, Cobus Toerien, Johan Rankin, Rubťn Urribarres, SAAF, TFDC,

DAAFAR Museum, Dassault Aviation and the many other people who assisted

me with this article.

Back to Aircraft Index

Copyright is alive and well,

please click

|